“Folklorist’s Progress: A Brief Biography of Warren E. Roberts” Warren E. Roberts was born, he was told, on the coldest day of the winter, February 20, 1924, in Norway, Maine. The house was a big one, the lower floor heated by a coal-fired furnace. A back stair rose from the warm kitchen, and a little girl, the new baby’s sister, climbed up it to ask why he was crying. He wants a cup of coffee and a doughnut, the nurse replied. Warren’s father was a saw filer; he kept the big saws whirling in a mill that used local birch to manufacture dowels for furniture and the tiny houses for Monopoly games. He remembers his father bringing home iron filings, screwed up in a twist of paper, and burning them in the kitchen stove to amuse the children with their glittering and sparkling. “Folklife,” he said, “was all around me.” Hilly, stony Maine was not suitable to modern farming but many farmers remained, and he recalls sleds pulled by oxen. Norway was famed for the crafting of snowshoes, and in Mellie Dunham and Eugene Andrews the town had two champion country fiddlers. Andrews also ran an antique shop out of an old barn, and he used to send Warren home with little gifts. There, perhaps, lies the origin of the inquisitive, acquisitive spirit that has created a vast collection of old tools. “Growing up in a town like that was just for me,” Warren said, “and I wish every child could have such a childhood.” Warren’s two older brothers followed their father into the factory, but Warren, valedictorian of his high school class, somehow always knew he would go to college. When the family followed the timber to Portland, Oregon, Warren wisely chose by architectural style and entered Reed College. His plan was to major in chemistry, graduate, and then teach chemistry to make the money to go to graduate school in English, but a kind advisor persuaded him to major in English. Attending a small high school, graduating in a class of fifty, was an advantage because all the students were urged into participation. It was not easy to gather eleven boys for a football game. Only two boys could be drawn into competition for an award in public speaking. Everyone was necessary; the excellent were rewarded. But it was also a disadvantage. The work was not challenging, Warren never had to do homework, and was not perfectly prepared for college. An avid reader, he got by on his knowledge of Mark Twain, but his study habits were loose, and the snows on Mount Hood called him. All of the Roberts boys were athletes. “Sports were more than a pastime.” Like his brothers, Warren played football, and he excelled at the weights in track and field, putting the shot, hurling the discus. But skating and skiing were his joy. The boys looked forward to the coming of winter when a farmer at the edge of town took down his fences. On his pastures, Warren learned to ski. When he left Reed College for the army in March 1943, Warren joined a ski troop—an excellent decision, for it led to an infantry career of three and a half years during which he never saw action. Before his division was deployed to northern Italy, he was selected for officer training, transferred to the Pacific, and at the war’s end he was in Korea. When his enlistment was up, he was asked to join the reserve, but resisting pressure, he declined—another excellent decision. As an officer, he had been asked to prepare a plan for withdrawal from the thirty-eighth parallel, and were he a member of the reserve, he would surely have been called back into action during the Korean War at just the time he was working on his doctorate at Indiana. Returning to Reed, pursuing English as his major, he found the fashionable new criticism baffling. His affection for literature had always been part of a larger attraction to social history. Studying Shelley’s verse in isolation from Shelley’s life and times seemed pointless; what thrilled Warren in Shelley was his radical orientation. He knew the coming spring would be red, not green. Literature and history were two of his loves. Music was the third. His mother, English by birth, was a lovely singer, and later he would tape-record her old songs for Stith Thompson. Warren, the bass section of his high school glee club, had starred in a production of H.M.S. Pinafore. To prepare the singers, the director, Miss Wood, had taken them to see a professional performance of Pinafore, still a rage in the state of Maine, and Warren, smitten, began the long enthusiasm for Gilbert and Sullivan that would make him a mainstay of amateur light opera in Bloomington. (Seeing him perform in The Mikado marked my daughter Ellen Adair, making her, like Roger Abrahams, a Gilbert and Sullivan devotee.) In the army, Warren befriended country-and-western musicians, learning the guitar. At Reed (where Gary Snyder and Dell Hymes were also students at the time), Warren combined his interests in literature, history, and music into a senior thesis on the ballad. Reed had just acquired a used copy of Child, and Warren’s teacher, V. O. C. Chittich, author of a book on local color writers from the Northwest and so a kind of folklorist, suggested he might do something with the ballads. Warren likes to call himself a gadfly. Intellectually contrary even then, he read that the ballads were tragic, so he counted them up, proved more were comic, and “pinned Gummere and Gerould to the mat.” In that thesis began the career of a great folklorist. He would elaborate its point in further study, contrasting the melodies of the comic and tragic ballads in a paper he presented at a conference in 1950 (when he was twenty-six), which naturally upset the guardians of ballad truth. From Oregon he wrote letters inquiring about graduate study in folklore to Berkeley, North Carolina, and Indiana. Receiving an encouraging reply from Stith Thompson, Warren came to I.U. for graduate work in English. He arrived on the Monon line at dawn, picked up his bags, and walked to campus. With a new lamp, bought at the bookstore, he claimed the lone desk in room 41 of the old library and there he wrote his dissertation. His first publication, a paper on Edmund Spencer’s use of a fable from Aesop, appeared in the Southern Folklore Quarterly. In his second year of graduate study, Warren was assigned the undergraduate courses in folklore, one a general introduction, the other American folklore—the ancestors of today’s 101 and 131. Below the untenured professors, the English department maintained a level for teaching fellows who were paid $2800 when instructors got $4000. As a part-time teaching fellow, Warren drew $700 a semester. That was 1949, so Warren has taught at I.U. for forty-five years. The year before, the course had been taught by William Hugh Jansen, but Jansen left for a new job at the University of Kentucky. Jansen used Botkin’s Treasury as the text for American folklore, and was able to enliven the class with the fieldwork he had done for his dissertation, the tall tales of Oregon Smith, which he collected at a filling station that stood where the Law School stands now. Warren had read widely in folklore, beginning in the summer before he came to Indiana. The books he consumed were mostly collections of texts. Warren also had Jansen’s course outlines, based in turn on Stith Thompson’s, which, modified by Warren and passed through his students and their publications, have shaped thousands of undergraduate courses in folklore. He had read, he had the outlines, but he had not as yet done the fieldwork that could bless the classes with life, and he hates, he says, to think what those first classes were like. At the time, Stith Thompson, the author of the successful survey of world literature for undergraduates, was dean of the graduate school. “Thompson had made,” said Warren,” the greatest mistake a teacher could make.” During the war, when students were few, he had put everything he knew into a book, The Folktale, and he had little left to teach. He began classes with reminiscences about famous folklorists he had known, then filled the remaining time with student reports. Stith Thompson suggested that Warren might examine Perrault’s tales on oral tradition, and he assembled so many versions of one story that his dissertation became a case study. Published in 1958 and dedicated to Thompson, The Tale of the Kind and Unkind Girls is a masterwork within the historic-geographic paradigm of folkloristic research. His Ph.D., delayed will he fulfilled his minor in anthropology and Stith Thompson passed a year in South America, was granted in 1953, and Warren joined the full-time faculty, teaching research techniques to composition students, world literature—Homer, Dante, Shakespeare, Mark Twain—to English students, as well as folklore introductions for undergraduates. When he was a student, Warren lived in the graduate men’s dorm, now named for the folklorist John Ashton. In the women’s dorms lived a talented pianist at work on her M.A. in music. Warren and Barbara both received their master’s degrees in 1950 and were married soon after in Connecticut. In 1959, Warren, and Barbara, and their two daughters went to Norway, the only nation in the Fulbright program that offered opportunities for advanced folklore study (as well as good skiing). Warren’s plan was to conduct a series of studies of Norwegian tale types, to determine oicotypes, and then plot their distributions to further understanding of regional dynamics. Despite the extreme difficulties presented by Norwegian dialects, he produced Norwegian Folktale Studies (1964), a book still used as a text in Norway. More important, while living in Norway, he visited folk museums, talked with scholars of material culture, and learned that his interests in furniture (he is a superb cabinetmaker) and architecture (he designed and finished his handsome home in Bloomington) lay within the domain of folklore research. Upon Stith Thompson’s retirement, Warren took over the folktale seminar, but in Norway he had found a new career. The abstract new concepts in narrative research did not interest him. Felix Oinas had showed him a translation of Propp’s Morphology in typescript. “Nonsense,” was Warren’s reaction. He was excited by the potential of material culture, so he happily surrendered the folktale class to Linda Dégh, when she arrived, and with Richard Dorson’s support, he began offering courses on art, craft, and architecture, and focusing his research on nearby Indiana. In the early 1960s, he was one in a small group of scholars whose work has made the study of material culture a major part of American folklore. (He and I were together on the America Folklore Society’s first panel on material culture, in Denver in 1965, memorable for an earthquake that rattled the meeting.) Today he is a leader in three professional societies—the Pioneer America Society, the Association for Gravestone Studies, and the Vernacular Architecture Forum—all founded since that time. Seeing the importance of the folk museum in Norway, he received a grant from John Ashton to visit American museums. At Winterthur, Charles Montgomery, a great scholar of furniture style and a pioneer of material culture research, told him there was no future in the study of folk art. So much in life is a matter of chance. Searching for clear lumber, Warren visited Wylie House, which was then being restored. Will Hardy, a master plasterer (with whose son, Junior, I used to play for square dances), directed Warren to Wally Sullivan who was down on his knees, nailing on a baseboard. Wally asked if he knew anyone who wanted a log cabin. Tearing that cabin down and erecting it for a neighbor, Warren learned how easily and economically and outdoor museum could be built. With Wally at his side, he gave, he says, the most productive years of his life to dismantling old buildings, working toward the creation of a folk museum for Indiana. Plans kept shifting, promised finances kept evaporating. The search for funds was heartbreaking, and his dream was never realized. But his close research led to a major work, Log Buildings of Southern Indiana (1984), and a battery of model studies of tools and craftsmen (his piece on the Turpin chairs, is, in my opinion, one of the finest papers ever written on material culture), many of them gathered into a book, Viewpoints on Folklife (1988). And it is his proudest claim, he says, that in his courses and his trips to southern Indiana he trained the next bright generation of students of material culture at Indiana. Warren Roberts’ career has been marked by signs of success: The Chicago Folklore Prize, a Guggenheim Fellowship, the Douglas Award of the Pioneer America Society. On his sixty-fifth birthday, his colleagues honored him with a Festschrift, The Old Traditional Way of Life (1989). A gentle, passionate teacher, a meticulous craftsman in the workshop and library, a good friend, Warren Roberts has created in his writings and through his students a monument to the workers who turned their daily labors into exhibits of skill and wisdom.

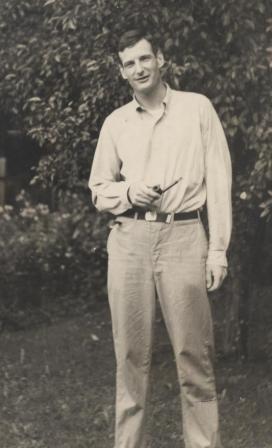

Courtesy of Patricia Glushko |